Normalization of Deviance and Central Banks: What They Were & What They've Become - Part I

Over the next four weeks, I will discuss what central banks were and what they've become. What central banks have become is completely different from what they originally were. In fact, anyone associated with the development of the Federal Reserve - which was only created in 1913 - would find today's Federal Reserve completely unfathomable. One explanation for this metamorphosis is 'normalization of deviance.' In this week's Part I of the discussion, I will describe what 'normalization of deviance' is and what central banks used to be. I will also provide a preview of what central banks have become.

NORMALIZATION of DEVIANCE

Seven-times Formula 1 driving champion - including five championships with Ferrari! - was once asked to explain his considerable wet-weather driving prowess. He explained, "the car is always talking to you, but in the rain - she whispers." (The photo below is from the rain-soaked 1996 Spanish Grand Prix, Schumacher's first win with Ferrari. As the pitboard indicates, Schumacher is almost 1-minute ahead of his closest competitors. The late, great Sir Stirling Moss said of that Grand Prix, "It wasn't a race. It was a demonstration of brilliance.")

Complex systems like nuclear power plants and advanced aircraft are no different than Formula 1 racing cars; they also speak. In all cases, the language these complex systems speak communicates how well and how poorly these advanced designs are operating. When dealing with complex systems like this, engineers use the phrase "normalization of deviance" to describe how formerly rare or even proscribed events first occur, and, over time, come to be accepted as normal and acceptable. A classic example that explains normalization of deviance that many people will be familiar with is the 2003 Space Shuttle Columbia disaster.

While the space shuttle featured many advanced features, the airframe itself was not much different than what you would find on an commercial airliner; it was largely built of aluminum. This structure - along with the astronauts themselves - required protection from the heat of re-entry. As the shuttle transitions from the vacuum of space into the earth's atmosphere it is traveling at a speed in the vicinity of Mach 25. The friction generated at these speeds creates an enormous amount of heat as the shuttle re-enters the earth's atmosphere. This heat can't be allowed to cause the shuttle's airframe to get too hot. Like all metals, aluminum rapidly loses strength as it gets hotter. If the aluminum gets too hot, then the airframe will not have the strength to withstand the forces imposed on it and the shuttle will brake apart.

The shuttle design relied on a 'thermal protection system' to keep the airframe from getting too hot. See the figure below and note how well the material insulates a human hand from the heat generated by a blow torch.

The thermal protection system was a single point of failure; if it failed, there was no back-up and the shuttle was doomed. In previous launches, chunks of ice and insulating foam had fallen off the space shuttle. The shuttle's main engines ran off of two cryogenic liquids - liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen - and the associated cryogenic systems could be prolific generators of ice, particularly in the high-humidity ambient conditions Florida is famous for. In many launches, falling debris had damaged the insulating tiles that protected the shuttle airframe from the heat of re-entry. At first - and for obvious reasons - this damage was a source of great concern. However, over time - and as this damage became more commonplace - it came to be accepted as normal. However, as the theoretical physicist Richard Feynman stated when investigating the first shuttle disaster, "nature can't be fooled." While attempting re-entry on 01 FEB 2003, Space Shuttle Columbia broke apart over Texas. She had been fatally damaged by a piece of falling insulating foam during her launch on 16 JAN 2003 and was unable to withstand the rigors of re-entry.

CENTRAL BANKS - WHAT THEY WERE

Historically, the "gold standard" of central banks, pun intended, was the Bank of England (BoE). What made the BoE so successful were its conservative practices. Whenever an individual presented currency to the BoE and asked to exchange it for gold, the BoE would do so without hesitation. It was the requirement to provide gold when asked to do so that forced the BoE to adopt conservative, prudent lending policies. These policies produced a tremendous amount of confidence in the British currency. People the world over desired to hold British currency because it had a record - eventually several centuries long! - of maintaining its value. There is a very interesting theory that holds the primary reason England was able to build and maintain an enormous globe-straddling empire was not its military might, or even its Royal Navy. Instead, it was the strength and international acceptability of its currency.

These conservative central bank operating practices are succinctly summarized in "Bagehot's dictum." Walter Bagehot was a British journalist of the mid-nineteenth century, and he summarized good central banking practice as "in a crisis a central bank can lend freely but only against good collateral and only at high rates of interest." The concept was that solvent firms - with sound, wealth producing assets - would be willing to borrow money, even at high rates, to manage a temporary shortfall of cash or temporary economic downturn. In contrast, unsound, speculative businesses - whose unsoundness was starting to manifest itself in poor business performance - would be unwilling to borrow money at these same high rates. By only providing credit to sound businesses, Bagehot's dictum helps to ensure profitable businesses have sufficient access to credit without giving rise to a false, speculative boom built on cheap money.

The legislation that created the Federal Reserve wasn't nearly as ambitious as the central bankers who would eventually run the Fed or the academics who would dominate the economics departments at Ivy League universities. The Fed was founded largely on "real bills" doctrine that was wholly consistent with the conservative central banking practices of the past, the BoE's in particular. According to real bills doctrine, central banks should only "discount" - or provide loans against - short-term, self-liquidating commercial debt. These loans should only be made after a commercial firm has exhausted all other sources of credit and must be made at a 'penalty' rate of interest; namely an interest rate higher than the rate prevailing in the free market. Real bills doctrine is completely consistent with Bagehot's dictum of a central bank only lending in a crisis and always lending at a high rate of interest.

The classic example of short-term, self-liquidating commercial debt is "commercial paper." In the normal course of conducting business, there can be a considerable lag between when a company spends money to manufacture a product, and when the company is paid by its customer for that product. For example, certain types of capital equipment - a large power production turbine or a very complex machining center - can take years to build. The manufacturers of this equipment may receive progress payments from their customers as the work proceeds, but these payments will only capture a small fraction of the costs incurred to build the equipment.

While the company is finishing its manufacturing and 'waiting' to be paid by its customer, the company must still pay its employees and taxes to the government. In order to meet these current demands for cash, companies will take out short-term, low-interest loans to cover short-term expenses while they wait to receive payments from their customers. The loans can be for terms as short as 30-days or less. Because the company will pay back the loan in full and not rollover the debt, any money that is created by the banking system to make the initial loan in the form of commercial paper, will be removed from the economy by the banking system when the load is paid back. This feature makes commercial paper type loans "self-liquidating."

Another aspect of real bills doctrine - at least as it was practiced by the BoE over many centuries and by the Federal Reserve for less than ten years - was the relationship the interest rate the central bank charged had to the rates set by the free market. Conservative central banking practice held that the 'discount' rate charged by the central banks must be higher than the rate borrowers could get in the free market. This was a crucially important point!

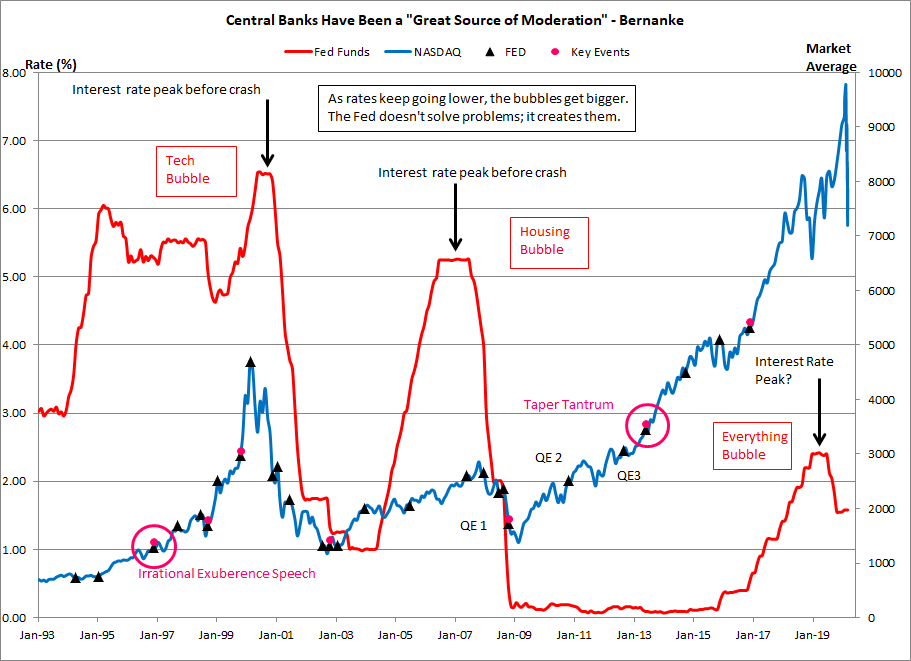

By setting its discount rate slightly above the market rate, a central bank operating under real bills doctrine would only have a minimal impact on the credit conditions in the economy. The central bank would be 'passive' instead of 'active.' Those projects that made economic sense would be able to access credit through the private banking industry. Prior to the "drunken sailor" doctrine of central banking as practiced and perfected by Alan Greenspan, Ben Bernanke and others, there used to be a stigma attached to asking a central bank for a loan. This stigma, coupled with the higher discount rate charged by a central bank, kept the proverbial lid on the wild, speculative lending practices that have become commonplace in today's central banking era. The central banks fueled bubbles of recent memory - three in just the past 20-years - could never have occurred under a conservative, passive central bank operating under a real bills regime.

CENTRAL BANKS - WHAT THEY'VE BECOME; A PREVIEW

In his invaluable survey of American economic history, Economics and the Public Welfare, the great Benjamin Anderson contrasts the monetary system before and after the founding of the Federal Reserve, and uses two economic crises to do so; the Panic of 1907 and the Great Depression. Anderson writes (p. 24);

In the United States, with our inelastic currency system, we had several unnecessary money panics. The panics of 1873 and 1893 were complicated by many factors, but the panic of 1907 was almost purely a money panic. Our Federal Reserve legislation of 1913 was designed to prevent phenomena of this kind, and, wisely handled, could have been wholly (beneficial). It is noteworthy however, that the money panic of 1907 had nothing like the grave consequences of the collapse of 1929. The money stringency of 1907 pulled us up before the boom had gone too far. There was no such qualitative deterioration of credit preceding the panic of 1907 as there was preceding the panic of 1929. The very inelasticity of our pre-war system made it safer than the extreme ductility of mismanaged credit under the Federal Reserve System in the period since early 1924."

At the time of the Panic of 1907 the US did not have a central bank of any kind. Anderson describes this as a 'inelastic currency system.' As a result, when the panic struck, the proverbial lender of last resort could only be found with great difficulty and there was a rather significant money panic; people literally could not find any money to borrow. However, as bad as the Panic of 1907 was, it wasn't remotely as bad as the Great Depression. There was a very specific reason for this and Anderson correctly identifies it. Specifically, the country was much better off without a central bank than it was with an 'active' central bank that would inevitably over-expand credit and fuel a wild, speculative boom that would inevitably go bust. This single passage completely explains how the Federal Reserve - especially during the Greenspan/Bernanke era - has visited one economic hardship after another on the average working person.

I apologize for not preparing an article over the last several weeks. Things have been very hectic lately but I am starting to keep a more regular schedule. I hope all of you are able to as well.

Peter Schmidt

Sugar Land, TX

April 19, 2020

PS - As always, if you like what you read, please register with the site. It just takes an e-mail address and I don't share this e-mail address with anyone. The more people who register with the site, the better case I can make to a publisher to press on with publishing my book. Registering with the site will give you access to the entire Confederacy of Dunces list as well as the financial crisis timeline.

Help spread the word to anyone you know who might be interested in the site or my Twitter account. I can be found on Twitter @The92ers